How each country’s emissions and climate pledges compare

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Financial Times has created a searchable dashboard of 193 countries’ historical emissions and future climate targets, providing information on the energy mix that indicates their progress on renewable energy.

The database is in its third iteration ahead of the UN COP28 climate summit, after being first published at the time of COP26 in Glasgow, using data from Climate Watch, the International Energy Agency and the UN.

Legally binding country targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are formally called nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and are recorded on the UN global registry.

These national commitments are required to be updated by 2025, when more ambitious targets will be needed in an attempt to limit the global temperature rise ideally to 1.5C since pre-industrial times, or well below 2C, as first agreed under the Paris accord in 2015.

Temperatures have already risen by at least 1.1C and the latest analysis by the UN Environment Programme has found the world is on track for global warming of up to 2.9C even assuming countries stick to their Paris pledges.

The UN secretary-general António Guterres has castigated the slow pace of progress, saying national pledges are “strikingly misaligned with the science.”

The 2023 is expected to be the hottest experienced so far, according to the Geneva-based World Meteorological Organisation, with records broken for sea surface temperatures, global surface temperatures and the retreat of Antarctic sea ice levels.

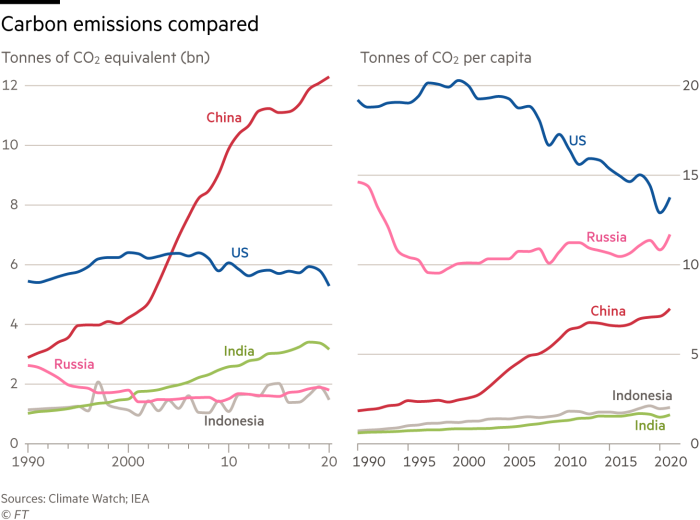

China remains the world’s biggest annual emitter despite a surge in renewable energy development, as it remains heavily reliant on coal for power.

It has set a goal for CO₂ emissions to “peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060”. This month it also pledged to track and detect leaks in methane, which holds more warmth than carbon dioxide but is shorter lived and regarded as the quickest way to limit global warming in the near-term.

China accounts for 26 per cent of the world’s CO2e emissions, followed by the US, India, Russia and Indonesia. Combined these five nations account for half of the world’s annual emissions.

The US, the second-biggest emitter on an annual basis but the biggest historically, has failed to improve its target in the past year, after the Biden administration in 2021 set an economy-wide target of cutting net emissions by 50 to 52 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

Its $369bn climate and tax legislation is expected to supercharge these efforts as energy and transport systems are transformed by subsidies, and could take it most of the way to its goal.

Some progress has also been made in Indonesia, where emissions declined by 23 per cent over the past year as renewable energy accounted for a greater proportion of its total electricity production.

The third biggest annual emitter, India, is struggling to make headway, after setting a goal in 2022 to reduce its emissions intensity by 45 per cent by 2030 compared with 2005 levels.

Emissions intensity is a goal that is criticised by climate experts because it allows for a rise in absolute emissions, as it measures emissions as a proportion of output.

The choice of different baseline years by country is another of the complexities in setting targets, making direct comparisons difficult. Baseline years often coincide with historical peaks in national emissions.

The less stringent measure of carbon intensity is also used by developing countries to design targets that allow for growth. It is calculated per unit of gross domestic product, to take into account the rise of emissions through economic expansion. China and India use carbon intensity.

Global carbon dioxide concentrations for 2023 are expected to near 420 parts per million, up about 50 per cent from an estimated 277 ppm in 1750, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In 2015, the year of the Paris accord, emissions from human activities were about 47bn metric tonnes of greenhouse gases, expressed as carbon dioxide equivalents. By 2022, this level was 57.4bn metric tonnes.

The UN climate chief, Simon Stiell, has urged countries to use COP28 as a “turning point”, stating that “governments must not only agree what stronger climate actions will be taken but also start showing exactly how to deliver them”.

Follow @ftclimate on Instagram

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments